Winner of the 2021 SAANZ Student Blog Writing Competition

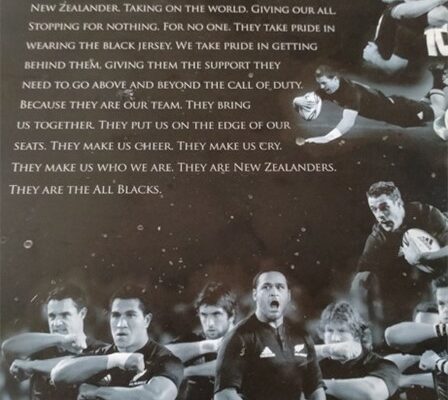

“The All Blacks are not just our heroes. They represent us as a nation. They epitomize what it means to be a New Zealander… They make us who we are. They are New Zealanders. They are the All Blacks. “

I read these words most days while eating breakfast.

My dad bought this commemorative Sanitarium Weetbix tin during the Rugby World Cup of 2011, a time when our national obsession with rugby was at its frenzied peak. While it provided my whole family with a good laugh about the ridiculousness of New Zealand’s obsession with the All Blacks, it’s also highly revealing about the role of sport in constructing national identity.

Every New Zealander knows that rugby is seen as an essential part of ‘who we are.’ Playing the sport is a rite of passage to many, a chance for boys to prove their mettle and be ‘real men.’

My boyfriend is one of many men who grew up like this. His father forced him to play rugby for the local club as he grew up, despite him hating every minute of it. It was a cultural ritual that held important symbolism about what makes a proper New Zealand man. It was valued more highly than any other extracurricular activity, despite my boyfriend being far more interested in music. This was because rugby has significance as part of national identity, while musical successes did not.

So, what is national identity? It’s a discourse involving an “imagined community” associated with a physical place and culture or group of people (Anderson, 1983). National identity is a link between an individual, the wider community, and the idea of a nation, an “emotional,” “kin-like” tie that forms a group of people, who may have little in common, into a homogenised community (Bell, 2017)

We experience national identity as natural. We don’t decide to be a New Zealander; most of us just feel that we are one. The fact that national identity is so common-sense to us shows how pervasive and hegemonic this discourse is. Through many factors, we feel that we have a claim to be a New Zealander. This claim often comes from identity markers such as having an ancestral tie, being born or raised in a country, or living there a long time. (Kiely et al., 2005)

Although national identity feels natural, it’s actually a social construction. This is what Benedict Anderson discusses in his writings on ‘imagined communities’ (1983). He describes nations as ‘imagined’ not because they are fictive but because most of the nation’s citizens will never meet, but still feel comradeship between them. (Anderson, 1983).

As a child, I always noticed how my dad would say “we won” after an All Blacks game. I always thought, “there’s no ‘we’ in this.” We’re sitting on the couch at home; how had ‘we’ won? Why were we associated with these men, who seem to have nothing in common with us? But through the construction of national identity, my dad (and most New Zealanders) felt a connection to the men out on the pitch, representing our nation. The content of media headlines interpellate us as national subjects, and by saying ‘we’ won, we are felt to be a homogenous group ( Bell, 2017). “When the all blacks…win an international game… ‘we’ feel a sense of pride at their success, again often despite not know any of the individuals concerned or being in any way involved. We feel their success is our success in some way” (Bell, 2017).

Sport makes national identity feel less constructed and more natural. When the All Blacks stand for the national anthem, we feel proud and patriotic. These feelings of patriotism, belonging, and solidarity distract us from national identity’s constructed nature and makes it feel removed from politics (Bell, 2017). We need to question national identity, as politicians and those with an economic interest draw on or manipulate these sentiments to create a narrative that suits their purposes. Corporations, such as Sanitarium and Weet-bix, draw on core national symbols and values to sell their products to consumers.

Essentially, the discourse of national identity has a vital role in validating the political state. Michael Billig’s theory of banal and hot nationalism explains this use of national identity (1995). Sport is a form of banal nationalism, a pervasive daily reminder of our role as national subjects. This banal nationalism primes us for instances of hot nationalism, when patriotism and nationalist sentiments are required from citizens, for example, when preparing for war (Billig, 1995). In this way, there is a strong link between the feelings of national identity that rugby creates and how politicians and others manipulate nationalistic feelings for events such as wars.

Another reason to be wary of the national identity discourse is that it involves exclusion and marginalisation (Bell, 2017). If the All Blacks represent us as a nation, then who is excluded from being a New Zealander? For example, ethnic and gender representation within our national sporting teams is an issue. If the All Blacks ‘epitomise what it means to be a New Zealander’, then is the ‘ideal New Zealander’ an athletic Pākehā, Māori, or Pacific Island man? What about women or people of other ethnic backgrounds? For example, Cas Carter (2016) notes that “22 percent of Aucklanders are of Asian descent and don’t have the cultural history…to dominate in a game like rugby.”. If rugby is essential in constructing our national identity, how can immigrants who may not be interested in the game ever be understood to be ‘proper ’New Zealanders?

Although I found this ‘commemorative All Blacks tin’ very funny as a child, now it also serves as a reminder of the pervasiveness of the discourse of national identity.

Let’s take the time to analyse the ways sport is used to create a particular narrative around national identity. Thus, we can be more critical when politicians, corporations, and other interested parties use these narratives to further their interests. It’s wonderful to feel a part of a community, but we must not let others tell our story for us.

Eleanor Pollard is a student at The University of Auckland

- Anderson, B. (1983), Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Bell, A., Elizabeth, V., McIntosh, T., & Wynyard, M. (2017). A land of milk and honey?; making sense of Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 57-68). Auckland University Press.

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Carter, C. (2021). If rugby’s just a sport, is NZ’s national identity at stake?. Stuff. Co.Nz. Retrieved 8 April 2021, from https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/opinion-analysis/80531453/cas-carter-new-zealands-national-identity-is-at-stake.

- Getty Images. (2017). All Blacks Team To Play Samoa Named [Image]. Retrieved 9 April 2021, from https://www.allblacks.com/news/all-blacks-team-to-play-samoa-named.

- Kiely, R., Bechhofer, F., & McCrone, D. (2005). Birth, Blood, and Belonging: Identity Claims in Post-Devolution Scotland. The Sociological Review, 53(1), 150-171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954x.2005.00507.x

- Pollard, Geoff. (2021). All Blacks Weet-bix Commemorative Tin 2011 Rugby World Cup. Image.